What "Arcane" Is Not

A Review of "Arcane": Part 4

(Part four of four. Spoilers for the animated series Arcane.)

NULLA.

In the previous essays we have treated the animated series Arcane as a monolith. We have presumed that the show should be recognized as a single achievement. Looking backwards and forwards, we have described Arcane as taking a consistent approach to the source material, and that both the lead-up to the Arcane War (summed up in season one) and the events of the actual War as such (in season two) represent a unified artistic vision.

Such assumptions, however, cannot survive actual contact with the show’s second season. The second season depicts the actual Arcane War, and it’s true that all the essential events make their appearance. Hextech and Shimmer combine to form the Arcane, Zaun collapses into civil war, a worsening drum-beat of terror attacks afflict Piltover, Piltover deploys chemical warfare against Zaun, a false prophet rises in Zaun, Caitlin Kiramman declares a short-lived dictator in Piltover, Jinx and Vi discover Vander-Warwick and an exasperated Noxian warlord formally invades Piltover to bring an end the crisis. But when this warlord—none other than Ambessa Medarda—allies in with Viktor, she provides him with his opportunity to fully awaken the Arcane, an event which she cannot know will annihilate Piltover and Zaun. Just before Viktor succeeds, Ekko—the “Boy Savior” of Runeterran antiquity—stops him. Finally, the show represents Jayce Talis and Viktor then somehow undoing the Arcane, and then disappearing with it. This ends the War.

If this breathless summary sounds like a lot of story to squeeze into nine episodes of television, that’s because it’s a lot of story to squeeze into nine episodes of television. Strict fidelity to events does not alone make a good story, and we see that rule in play in season two. As we’ve explored in the previous essays, the first season of Arcane appears to structure the cause of the Arcane War as the failure to sacrifice Jinx for the sake of peace. But in season two, Arcane adopts a different approach to the War.

The most obvious difference between the two seasons is politics. As other writers here on Substack have mentioned, season two’s politics stray into something like an apologetic for state power. This is because in the course of the events of season two, the intractable political crisis of the two cities almost entirely vanishes, and for no clear reason. The flint-eyed treatment of the nation-state and capital, the harrowing depiction of trauma and psychosis, and the anthropological theory of sacrificial violence are here mostly absent. Not entirely, but mostly. The show insists that the political crisis in Piltover and Zaun resulted ultimately from misunderstanding and malicious third-party actors (the Noxians). This is substantially different from the politics of the first season.

For instance: while it’s certainly true that certain now-legendary figures in the Sister Cities moved desperately to oppose the Arcane, how this affected Piltover and Zaun is obscured. Heroes as ambivalent towards each other as Jinx, Ekko, Vi, Caitlin Kiramman, Mel Medarda, and Jayce Talis really did succeed in creating a shaky eleventh-hour coalition against Ambessa and the Herald of the Arcane. But the show represents this coalition as mending the divisions of Piltover and Zaun. That’s clearly not what happened, even in the marginalia of the show. In order to stop the Arcane, these characters attempted to destroy the technologies that enriched and protected both cities. The Arcane might have been stopped, by Shimmer and the Hextech that created it still exist when the show ends.

When Jayce tells Piltover he intends to destroy the Hexgates, Arcane never clearly shows the viewer how the Great Clans—who have depended on the Hexgates for their stupefying wealth for a decade now—fled shrieking into the arms of Ambessa Medarda. Nor, for that matter, do we see a single Chem Baron observe Ambessa’s advance against Piltover with relish, gladly providing her with key amphibious landing grounds in exchange for certain guarantees. Instead, Arcane suggests that every political and economic motivation at play in the sister cities in season one has been replaced by an abrupt, warm regard between the two desperate cities.

I.

Admittedly, it’s not all incoherent. In fact, season two does come out swinging. Whereas at the end of season one, Jinx was grimly committed to jinxing Piltover and Zaun’s ruthless ambitions, in season two we immediately see Jinx’s human frailty overcome that heroic decision. Whereas before Jinx had accepted the necessity of killing her father Silco, now Jinx voices her regrets.

It’s not just about personal loss. Zaun is about to fall into chaos, and Silco is the only one who could have put it back together again. Jinx feels the weight of what she has taken from Zaun, and thinks, Maybe this wasn’t a good idea. Maybe I’m not a good idea. It would have been somewhat unbelievable if Jinx didn’t relapse back into her self-destructive thinking at some point. After all, without Silco to guide her, Jinx is for the first time totally alone. Every decision she makes is now only her own. No one is telling her what to do. Not Vander, not Vi, and not Silco.

“It’s so quiet,” Jinx says. “What am I supposed to do with that?”

At the end of season one, Jinx chose to embrace the jinx. But that doesn’t mean her demons spontaneously vanish. In fact, her psychotic breaks will reappear once or twice. Jinx has chosen her course, but her journey has only just begun. The second season asks whether Jinx can continue to take responsibility without sliding back into a world of self-delusion.

Without Silco, the Chem Barons turn on each other. While Jinx wanders the streets anonymously, Zaun’s streets erupt with bloody violence. (The show goes so far as to hint at child-trafficking by the Chem Barons Silco appointed.) Jinx mopes to the bitter beat of “Sucker” with the trademark, vacant look of the newly sober unused to life in the raw. The “sucker” of the soundtrack may refer to Silco, but Jinx helped him build this empire. Now Jinx has revealed the folly of what she helped her father create in Zaun, initiating its bloody fall. This is what they really created, not the false order of before. Indeed, the Zaun Silco created will now gladly either kill or turn the traitor Jinx over to Piltover in a heartbeat.

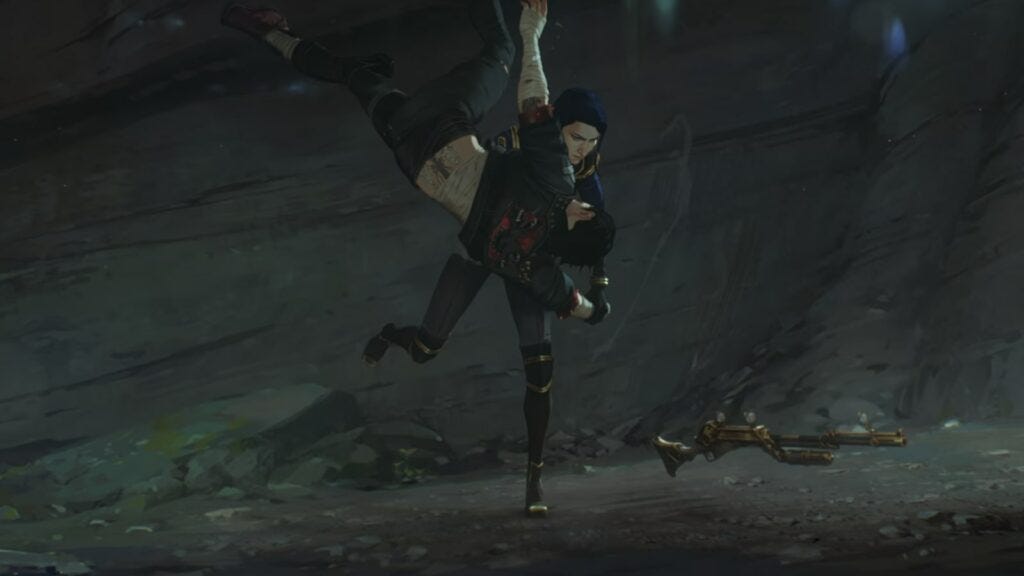

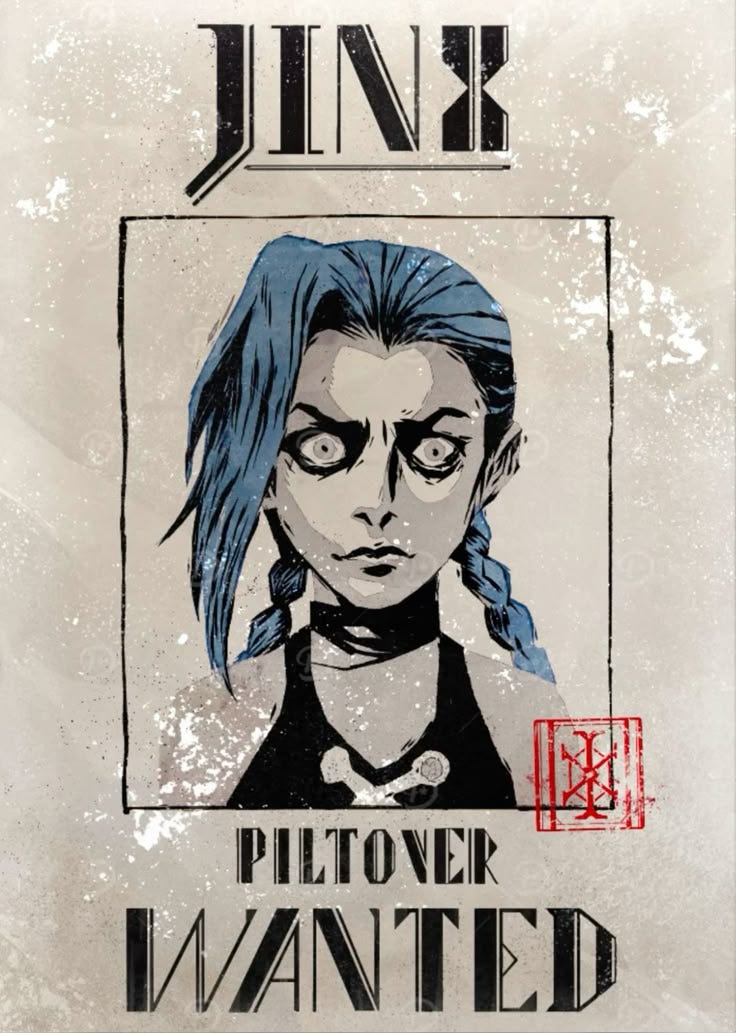

But Jinx has chosen a different path. She will not build her own empire in Zaun. She is still the jinx. What’s left for her, instead, is a long process of change and growth away from what she had been and what she had done. It’s also a process of self-recognition. Jinx notices her wanted posters and stares mournfully, like Mulan into her pond. “Who is this girl I see,” etc.

But perhaps she’s not the only abomination in the world. During this scene, we follow a young child fleeing from some sinister-looking gang members—just one particularly sharp example of the suffering Jinx has unleashed in Zaun. This fleeing child lands in Jinx’s arms. Whereas through most of this sequence Jinx’s self-recognition has necessitated a healthy, self-protective solitude, the fleeing child represents the other side of the jinx. Jinx is not the only person the world could gladly do without. When this abandoned and exploited child falls, Jinx literally breaks their fall. Life goes on, apparently. Jinx blows away the pimps and takes in the child.

Their name is Isha, and they will go on to champion a true resistance to the Chem Barons and Piltover alike, a resistance colored blue in symbolism of Jinx. Jinx is less sanguine. She points out to Isha the tension in any such resistance: “If you ever need to curse sibling, a family, or a society—my card.” She points to the wanted poster and tries to walk away. But Jinx has genuinely changed, and will befriend Isha. That does not mean life becomes easy for her. In fact, it’s only when we take responsibility for our life that the pain really starts.

With the glaring exception of its ending, Arcane’s second season is about how no one can walk away. Consequences come home to roost. The long-promised apocalypse of Piltover has finally arrived, and it’s not just abstract. Jayce Talis’s Hextech technology has merged with Silco’s Shimmer, becoming something sentient and malevolent: the Arcane. Ekko, the anarchist defender of the old Zaun, explains to Jayce that the Hexgate has been poisoning Zaun.

Now, it’s not exactly clear how poisonous goop accreting to the gears of the single most financially important machine Piltover has ever produced has been missed by maintenance. One might also legitimately question the logic of building the Hexgate engine in Zaun when it is easily accessible by angry Zaunites. Such mistakes in detail will accumulate throughout season two. But in any case, the appearance of the Arcane is far worse than the poisoning of one community. As the show’s scientists quickly discover, the awakening of the Arcane threatens Piltover and Zaun with total annihilation.

But the wheels really fall off for the show whenever season two turns its attention to Vi and her relationship to Piltover. As the reader might recall, Vi spent her formative decade in Stillwater Hold being pulverized by Piltover Enforcers. Torture would not be too strong a word. Season one treated this police brutality so matter-of-factly that when Caitlyn first discovers Vi, Vi cracks a joke about getting the beating over with so she can enjoy the rest of her night. The warden of the prison also jokes to Caitlyn that he’s lost count of how times they’ve beaten Vi. But now, in season two—chronologically, a maximum of two weeks later—Vi wears an Enforcer uniform.

When Jinx sees her older sister again, she can’t believe it. She reminds Vi that the badge she now wears was worn by those who had gunned down both their parents. “I’m tired justifying my choices to you!” Vi shouts. One might well conclude the outburst is because she can’t justify her choices. Anyone who has played League of Legends knows the background reason. In League, Vi is a Piltover Enforcer. That’s her character identity. Nevertheless, with how the show has presented her character so far, it strains believability that a long-time victim of such brutality would ever so much as touch an Enforcer uniform.

Of course, the show does give us the one possibly persuasive reason why Vi does so. Vi falls in love with Caitlyn Kiramman, the Enforcer who gets her out of prison and helps her get revenge on Silco. Even so, though, it’s an implausible relationship. In one sense, it’s true to form for Arcane’s psycho-political drama. Whether it’s classical Stockholm Syndrome or not, the psychological undertone of Vi and Caitlyn’s relationship is clear. Jinx has grounds to be disgusted. When Jinx’s attack kills Caitlyn’s mother—who helped fund Stillwater Hold—Vi has to choose between Jinx and Caitlyn. She chooses Caitlyn.

“My sister is gone,” she tells Caitlyn. She will then go on a “black ops” tear hunting Zaunites in order to find Jinx.

This may be the most egregious “what?” moment in Arcane. I won’t rehash my treatment of sacrificial violence or the debate about the “justice” of Jinx’s actions from the previous essay. But Vi does not need a degree in the mechanics of mimetic desire to understand the horrors of Piltover’s increasingly ruthless police state. She lived it. The viewer has to strain for an explanation for Vi’s actions. Does Vi not see Piltover’s cruel and unusual regime as the fault of the Council that funds it? Or does she reduce that apparatus to merely what happened to her as the result of Silco’s own corruption machine? After all, it was Silco’s catspaw Sheriff who dropped Vi into Stillwater in the first place. Does Vi believe that Piltover’s evils begin and end with Silco? That’s a shocking delusion—yet at least a believable one. Yet Vi never vocalizes such an idea, so the viewer is left with other, less impressive motivations. Vi appears to take Jinx’s attack on Piltover leadership at face value. Vi appears to be motivated by misplaced guilt and, well, sex. This makes it difficult for the audience to sympathize when Caitlyn abandons her.

But this weird representation of Piltover’s Enforcers goes beyond Ciatvi. In general, season two shies away from depicting state violence with anything like the frank horror of the first season. Even the season’s most vivid condemnations of state power are softened. For instance, one scene in episode four swaps back and forth between two moments that occur simultaneously. The first scene somberly observes Caitlyn mourning her mother, quietly laying down a memorial candle. Meanwhile, in the second scene, Caitlin’s agents torture a Zaunite. The show quickly swaps between the two scenes. The back-and-forth only lasts a few seconds, but if you don’t blink you get the point. Jinx avoided a similar fate last season. Liberal empires collapse into autocracy when their wealth is threatened; and aspiring autocracies need martyrs in order to suspend civil liberties and legitimize extraordinary violence against their populations. This sequence demonstrates this dynamic vividly.

Nevertheless, the same scene also lifts the responsibility for this violence from Piltover’s shoulders. The torturers are Noxians, not Piltoverans. In other words, while season one represents Enforcers beating Zaunites as so commonplace as not to be commented upon, season two has to apologize to the viewer for representing the expansion of Piltover’s state power by showing those doing the extra-judicial tortures as Noxians, not Piltoverans. In other words, it’s the Noxians who have corrupted Piltover’s noble ideals. The show implies that Caitlyn’s police state on its own would never allow such torture to happen. This is not just absurd, but a disturbing apologetic.

Again, throughout season two the political crisis between Piltover and Zaun has been reduced to miscommunication and exceptional bad actors. Whereas the first season appeared to see this crisis as something to meditate on in the form of Jinx’s jinx, the second season argues that this crisis will be largely resolved the instant the Noxians are driven out of Piltover. Piltover, the second season suggests, is not ultimately responsible for her actions towards Zaun.

II.

But the second season does something else, something even more peculiar than an anemic representation of a political crisis. Please forgive—or at least blame Arcane itself for—the following digression into the multiverse and why the show’s choice of it as a theme matters.

Arcane is a fantasy narrative. The plot of the show follows Piltover in its hubristic attempt to turn magic into a tool of empire. To do so, Piltover had to mechanize magic; and this mechanization resulted in the technology called Hextech. Hextech extended Piltover’s commercial empire to all corners of the globe. Simultaneously, Zaun developed Shimmer for the same reason: to construct a state apparatus capable of going blow-for-blow with Piltover. Throughout its first season Arcane questioned what the hidden cost of such technologies would be. When Piltover’s Hextech and Zaun’s Shimmer interacted, we found out. Hextech and Shimmer combined to become what the show calls “the Arcane”.

As we recounted in our first essay, the Arcane is the great mythic terror Piltover’s Founders had tried to bury forever. But eventually politics and the reasons of state made the first steps towards the Arcane advantageous for both Piltover and Zaun. Hextech arose in Piltover and Shimmer in Silco’s new Zaun. Season one insists that technology, while a natural human capacity, cannot replace a genuinely humanistic politics. Indeed, ever-increasing precision in mechanistic technologies proved to be a boon both the state could not live without.

But in season two, the Arcane has other properties than just corruptive power. The Arcane allows travel to alternate universes. Jayce, Heimderdinger, and Ekko are all teleported to such alternative timelines. Jayce lands in a potential future where Piltover and Zaun have been annihilated by the Arcane, and Heimerdinger and Ekko appear in a Piltover and Zaun miraculously and blissfully unified in a steampunk utopia that never developed either Hextech or Shimmer. The contrast is the point. Ekko is shocked to discover his archenemy, Jinx, never became Jinx in this timeline. Silco and Vander reconciled, which meant Vander and Benzo both lived, which meant that Powder never had to save anyone, which meant that everyone is alive—except for Vi, who Powder accidentally killed, setting in motion this whole series of events. The unsettling implication is that this timeline depends for its utopia upon Vi’s death. Nevertheless, despite killing her sister, the rest of Powder’s family remains intact. Powder does not lose her mind. There is no Jinx—and no jinx.

Why does this matter for the show? Well, it provides a different explanation for the consequences of Piltover and Zaun’s conflict. At first glance, the entire digression seems pointless. Ekko and Heimerdinger learn nothing about the Arcane that Jayce doesn’t learn from the sorcerer. Other than Ekko’s new “jump-drive”, he brings nothing with him from the alternative timeline.

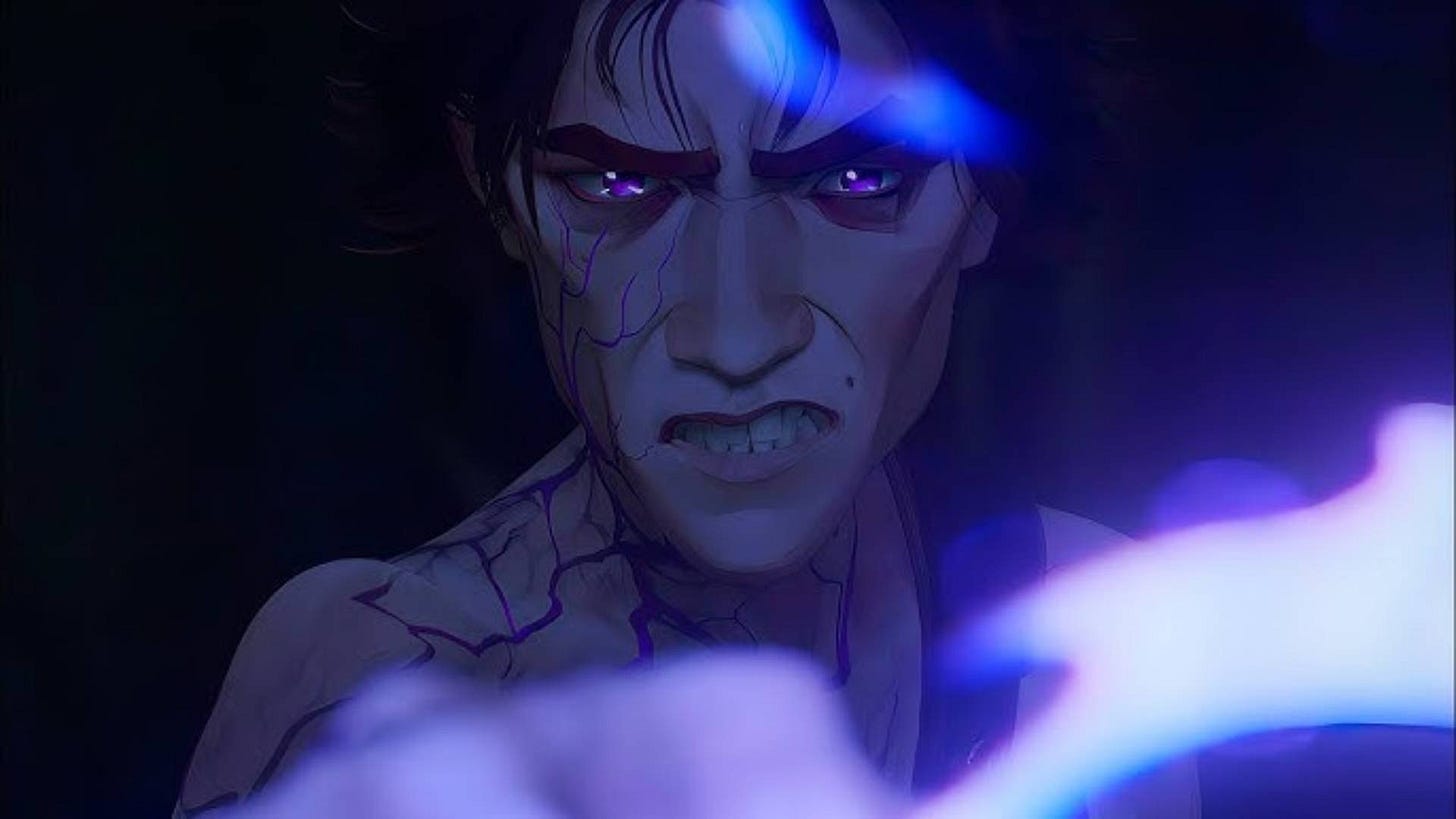

But Jayce gives us our key clue, and it suggests to us something about what the second season’s themes are. Jayce’s experience in this alternate reality results in him becoming convinced that his best friend Viktor must be destroyed at any cost. In fact, the show withholds the last key bit of information Jayce learns until the final moments of the show. That monumental detail is this. The sorcerer who summoned Jayce through the Arcane to show him the annihilation timeline—the same sorcerer who saved him and his mother and gave him the wild rune in the first place—is Viktor.

Here’s the deal. In the annihilation timeline, Viktor wins the Arcane War. As we noted, Ambessa Medarda creates a coalition to conquer Piltover outright so that she can control the Arcane. This coalition includes a very changed Viktor. (Weirdly, the shrewd Ambessa Medarda never appears to doubt her control of her ally, despite being the obviously weaker partner. But in any case…) In this timeline Viktor wins, and Ambessa along with all of Piltover and Zaun are destroyed by the Arcane.

Then, his ultimate victory won, Viktor apparently sits on a rock for something like several thousand years. Eventually, he has the (shocking) revelation that mind control and annihilationism give him nothing to live for. Therefore, as Viktor monologues near the end of Arcane’s runtime:

I thought I could bring an end to the world’s suffering. But when every equation was solved all that remained were fields of dreamless solitude. There is no prize to perfection, only an end to pursuit. In all timelines, in all possibilities, only you can show me this.

Finally we get to the root. The reader might have put it together already. The “you” here is Jayce Talis. A montage sequence shows the sorcerer repeatedly dropping the wild rune into child Jayce’s hands. We are never shown explicitly that the sorcerer who saved the childhood Jayce is Viktor, but the implication is pretty strong. Viktor has been traveling back in time to give Jayce Talis the wild rune. He does so to prevent alternative reality versions of himself from succeeding in destroying Piltover and Zaun. Therefore Viktor’s love for Jayce is an eternal dance backwards and forwards in time that culminates in present-day Viktor’s surrender of the Arcane that he thought would end the world’s suffering.1 Jayce and present-day Viktor then labor to unravel the dystopian technology they have created. When they succeed, they embrace and together with the Arcane vanish from existence. Piltover and Zaun are saved.

III.

In short, the theme of technology changes between the two seasons. Throughout season one, Arcane represented technology as a false panacea for political, relational, and personal crises. Silco turns to Shimmer to destroy Piltover and ends up transforming Zaun into a grotesque, fun-house mirror image of the very Piltover he hates. Viktor experiments with Hextech until he kills the very assistant who loved him. And so on. But in season two, Arcane shifts course. Technology becomes the solution to the show’s political, relational, and personal issues. Specifically, the very technology the show had represented with horror—the awakening of the Arcane—becomes the final means of resolving the show’s cycles of violence. Once the characters of the show encounter the multiverse, their character arcs finally resolve. They do so through the Arcane Hextech and Shimmer have created.

I’m not exaggerating. Jayce, Viktor, Heimerdinger, Ekko, and Jinx all change after encountering the multiverse through the Arcane. Heimerdinger is humbled out of his liberal pride by a hundred-year exile in a utopian timeline. Ekko’s shorter time in the same place causes him to lose his bitterness towards Jinx, resulting him trying to “save” her one last time. Jayce is shown that his actions will bring about the end of the world. And Viktor is told he will do the same by none other than his future self. Each character swerves away from the apocalypse solely because they encounter the multiverse.

As for Jinx, she too resolves her personal crisis. In the course of season two, Isha dies protecting Jinx. This finally pushes Jinx over the edge. For the first time she prepares her suicide in cold blood. It’s not a stunt any more. Jinx surrenders to despair. But when Ekko tries to stop her, he succeeds because he has a time-travel device. She’s not convinced by his arguments. But what she is convinced by is noticing that Ekko’s device has her own trademark little monkeys. Alternate universe Powder had helped Ekko build this device. Jinx may have lost Isha, the subtext suggests, but out there, somewhere in the multiverse—accessible only through the Arcane—there is a happier, more beloved Powder. Suddenly, Jinx is no longer suicidal. She is—for some reason: I admit I don’t quite understand why—given hope by the fact that a version of herself that did not live the life that she lived exists in the multiverse, happy and fulfilled.

In each case, frankly, the irony leaps off the screen. The Arcane enables the main characters of the show to finally arrest their destructive patterns. This is only possible through the meditation of the very dystopian technology which brought about the doom of Piltover and Zaun. Viktor does a good job summarizing this disquieting idea. He monologues:

That which inspires us to our greatest good, is also the cause of our greatest evil.

That this quote is banal—if not totally meaningless—never seems to occur to the show-runners. But the banality aptly summarizes the second season. Characters change because they realize that in a multiverse, what has occurred will always occur everywhere, all the time. This wisdom is granted to each character by state-sponsored technologies. And if those technologies harm others, then it’s a price—a sacrifice, even—the characters are willing to pay in order to grow.

Perhaps I’m being overly harsh in my interpretation. That’s a possibility. However, to me, representing a healthy character change solely through an encounter with technology will always be disturbing. We are who we are from our real relationships with others, not a series of abstract potentialities. In season one, the cost of such technologies was both human beings and humanity as such. Season two claims the opposite idea. Technology has replaced spiritual introspection. Our salvation, if we have one, lies in technology.

It’s more than the theme of technology that has been reversed. For instance, by the end of the show Jinx has decided her death is necessary in order for Vi to be with Caitlyn. (In fact, this does not appear to be actually true, as Caitlyn appears to accept Jinx for who she is in the penultimate episode.) Jinx sacrifices herself to destroy Warwick, but it’s more-so about no longer taxing Vi with Jinx’s presence in her life. Of course, Jinx doesn’t really die—Caitlyn discovers that she didn’t—but that’s the conclusion of Arcane. Sometimes, we must destroy ourselves so that our sisters can have the Enforcers they’d like to have.

It’s no fun to dwell on a downer. We’ll wrap up with a couple final observations. The revolution in Jinx’s character arc is not the only bizarre conclusion the show-runners go for. Viktor’s time travel paradox, Ekko’s shallow change of heart towards Jinx, Ambessa’s amazing folly in trusting an all-powerful Viktor, Sevika miraculously joining Piltover’s Council, the show’s insistence that Vander and Silco could have reconciled, and Vi’s inability to grow beyond a pathological dependence on others all fail not only to satisfy but even to convince on a plot level. For a show that once treated the confluence of politics and personal relationships so carefully, season two proves an incoherent and disappointing conclusion. Fans have wondered if Riot Games simply told Fortiche to hurry up and finish the show so that they could move their media engine to somewhere else in Runeterra. In light of how Arcane ended, it would not be surprising if this were true.

Arcane has received little critical attention. In fact, for a show that is #17 on IMDB—between The Office and Better Call Saul—it has received almost zero critical attention beyond Substacks and blogs. Nevertheless, it is a show with story contributions from artists of the stature of Sting, Imagine Dragons, Pusha T, JID, Linkin Park, and Twenty-One Pilots, a show that was at one point one of the most streamed shows on Netflix, and a show that is, in any final analysis, an exploration of how liberal civilizations collapse. It is beyond this author’s expertise to say why Arcane remains neglected. But what I might say is this. If Arcane had held to at least some of the serious ideas it explored in season one rather than abandoning them, the show may have had a stronger chance at coming into its own as a meditation on issues central to the twenty-first century.

But that would be to say what Arcane is not.

If you enjoyed this post, consider donating to support my work.

This is an example of the “Bootstrap Paradox”, one of science fiction’s laziest methods to resolve time travel plots.